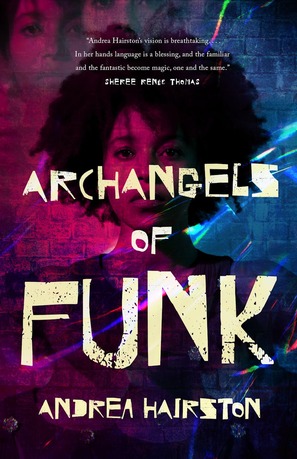

Andrea Hairston, ARCHANGELS OF FUNK

I received an advance copy of Andrea Hairston’s Archangels of Funk, in return for giving an honest review. Here it is. The book will be published in two weeks or so.

Andrea Hairston’s new novel, Archangels of Funk (2024), is a science-fictional sequel to her two previous magical realism / alternative history novels, Redwood and Wildfire (2011) and Will Do Magic for Small Change (2016). The new novel’s heroine, Cinnamon Jones, is now a sixty-year-old woman; those previous novels were about, respectively, Cinnamon’s grandparents (a Black grandmother and a Seminole/Irish grandfather) who leave the deep South and come north to Chicago during the Great Migration of Black people in the first half of the twentieth century, and Cinnamon herself as a teenager in Pittsburgh in the 1980s.

This places Archangels of Funk as occurring in 2030 or so. This is only a few years beyond the actual present in which the book was published, and in which I am writing this note. But things have changed radically during those several years. We have gone through the Water Wars, which are not described in detail in the novel, but which evidently shook things up quite a bit. Large corporations and rich white people still own the world; but not everything is under their control. Cinnamon Jones is part of a thriving multiracial alternative community, including farming cooperatives and centered on the Ghost Mall, a former shopping center now refurbished as a collective gathering place and free kitchen, with lots of space for experimental collaborative projects. This community is hooked in to the global Internet, but it is largely a loose, local aggregation, autonomous from major centers of power and production, more or less self-sufficient in terms of food, and largely reliant on bicycles for transportation, instead of cars. This community is also relaxed and dispersed, resistant to the sort of centralization and totalization that one often finds in both utopian and dystopian visions.

Archangels of Funk is narrated in close third person through the varying perspectives of Cinnamon herself, her close friend Indigo, her dogs Bruja and Spook (both of whom seem to be able to grasp spoken human desires and suggestions, and the latter of whom is cyber-enhanced), and even her three “circus-bots”. These sentient machines are camouflaged, when they are quiescent, as piles of junk; but when they awaken they take on robotic animal forms, and project vivid multimedia spectacles. They are also imprinted with the personalities of Cinnamon’s grandparents and great-aunt. The circus-bots preserve and transmit the wisdom of the ancestors, but they also plunge forward in time in order to generate exuberant new configurations of spectacle.

Hairston is less concerned with narrative than with exploring the textures of everyday life in the changed circumstances of the world that the book presents. The novel is set in just one locality, western Massachusetts, where Hairston herself actually lives; and it takes place over the span of just a few days. Cinnamon is mostly concerned with staging her yearly extravaganza, the Next World Festival. This is a “community carnival-jam”: a gigantic theatrical spectacle, highly participatory, played in an outdoor ampitheater, and filled with song and dance, as well as with seeemigly magical masks and costumes, together with splendiferous props and sets. Everything in the Festival both calls back to African American history and leap forward to envision social and personal transformations. A Mothership lands, recalling George Clinton and Parliament/Funkadelic. Careful planning serves for the proliferation of play, rather than for any more instrumental purpose.

Cinnamon is by no means anti-technology. But she is careful with her gadgets and inventions, because she is all too aware of how computational devices in the 21st century serve purposes of dissuasion and surveillance. Her house is configured as a Faraday cage, and she never carries or uses a cellphone. Her bots are always gather data, and anxious to give advice; but they are also booby-trapped to prevent corporate spies from seizing and reverse-engineering them. There is also considerable attention paid to physical safety. The surrounding woods are rife with robbers looking for a quick score, as well as with “nostalgia mlitias,” dudes roaming about in combat gear trying to bring back the old days of MAGA values. But their efforts are somewhat hampered, fortunately; though they seem to have lots of guns, they are mostly empty because bullets, bombs, and other munitions seem to be quite scarce.

Cinnamon and her friends are not just happy-go-lucky creators, however. They suffer from depression, relationship problems, bouts of fake nostalgia, and other all too real psychological symptoms. The ill effects of global warming are everpresent: “deny climate change all you want, but when that brushfire rolls up on your ass, you run or burn“. There are also kids whose parents are missing, visitors with murky and perhaps dangerous agendas, and so on. The novel is, at least in part, about how to negotiate such difficulties. It is psychologically incisive, even as it values lateral connections with others over the narcissism of deep interiority. Cinnamon is adamant that she is “too busy” to be “waiting for love,” but she remains open to chance encounters and unexpected opportunities. People always seem to be engaging in

Archangels of Funk has no deep, mythical narrative, no grand, overarching Story: this is precisely because everything in the book is composed of little stories, told and experienced, involving exchanges and transformations on multiple levels. There is no firm line between actuality and dream, or between technology and magic. Hairston’s prose style strikes me as unique, and it is ultimately what draws everything together. The writing is liquid and mercurial, stopping to capture unexpected details, passing between interior monologue and physical description, then turning and flowing away from what you thought was important, and drawing your attention somewhere else. When I finished reading Archangels of Funk the other night, I felt a bit confused because I was hoping for more. The final dialogue, between Cinammon, her bots, and some long-ago friends who have shown up long after she expected never to see them again, suggests a never-ending adventure. You may become tired of adventure and seek to rest for a while, but the energy will return, at least until you have passed (as all people and all things ultimately must). “You’re a dream the ancestors had” — which is true enough, except vice versa is true as well. “We’re in a sacred loop”; there is no goal except continuing to play and to circulate. “Nobody makes up their own mind,” because our minds like are bodies are continually in motion, continually intertwined with others. (Earlier, we had been told that “mind was always a community affair”). And: “here we are at the end of the world,” Cinnamon finally says, “thinking up what the next world will be.” And: “I am who we are together.”